How Brexit could drain Britain’s bottled mineral water industry dry

Shutterstock Alexandre Nobajas, Keele University

The European bottled water industry is one of the most controlled sectors in the food and drink business. There are norms regulating everything from water quality to what labels should look like. It’s a multi-billion pound business, in which thousands of brands compete to entice consumers. It’s also a growing sector which has surpassed the once almighty soft drink industry in size.

All this dynamism, however, is likely to be strongly affected by Brexit.

The bottled water industry is highly sensitive to changes in the relationship between the UK and Europe. That’s because all regulations regarding bottled water are decided at EU level, with countries then adapting them to their legal frameworks. Therefore, unless a specific arrangement can be made by 30 March 2019, when the UK is set to leave the EU, British water producers will have to stop selling their products in Europe.

What’s water?

The main set of regulations establishes that there are three types of bottled water.

Natural mineral waters have to be waters which come from a single underground source and have a distinctive taste – although this may only noticeable by connoisseurs. They have a specific and stable mineral composition, and must be bottled at source. They are strictly regulated and only those which pass all requirements may be recognised and included in the official mineral water list, which is periodically published by the Official Journal of the European Union. According to the European Federation of Bottled Waters, natural mineral water accounts for 83% of the bottled water produced in Europe, making it the most popular type of bottled water. In several countries, such as Austria, Italy and Germany, almost all consumed bottled water is of this type.

Spring waters are similar in every aspect to natural mineral water but their mineral composition doesn’t need to be stable and there is neither a formal recognition process nor any official list. They are not very common in Europe, making up just 15% of overall production, but in the UK they are comparatively much more popular, accounting for 28% of production.

The term bottled drinking water, also known as table water, refers to anything that isn’t natural mineral or spring water. That includes groundwater which is treated and tap water which is sold bottled – but it must be safe to drink. In Europe, it is the least popular type of bottled water, with only 10% of total production being of this type. In the UK, however, it is a bit more successful, making up 18% of production.

Regulation

The most successful type of bottled water – natural mineral – is also the most regulated by the EU. This is therefore the type of water which is most jeopardised by the Brexit process, as in theory, only those recognised sources which are within EU countries can be sold in the EU.

The European Commission has warned that, after Brexit, all British natural mineral water producers will be considered as operating from a “third country”. That means they will not be recognised as European waters and won’t be able to export their water to the EU unless a general Brexit withdrawal agreement, or at least one focused on the natural mineral water sector, is reached.

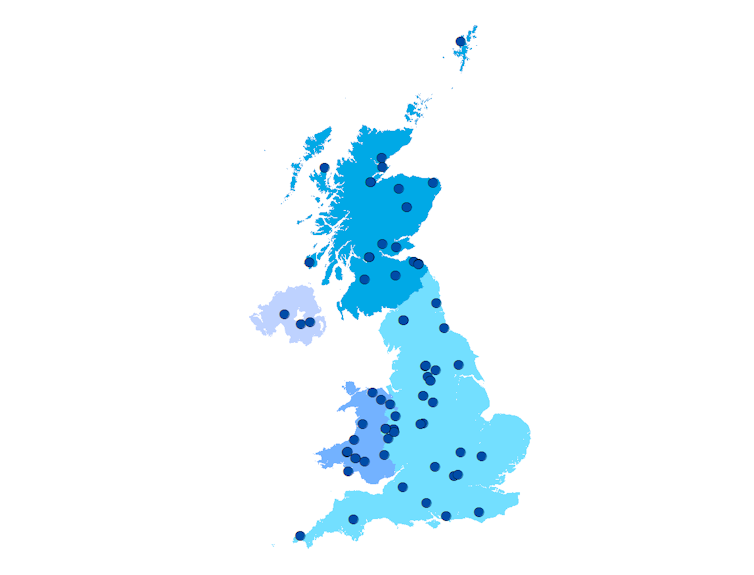

The UK currently has 86 recognised sources which can be used to bottle mineral water and they are located in 61 locations across the country, from St Ives in Cornwall to the remote Northmaven peninsula in the Shetland Islands. Although it is difficult to find out how much this type of bottled water is worth in the UK, it is estimated that the total worth of the sector is £2.7 billion.

The UK’s natural mineral water sources mapped. Author provided

The sources are often rural and also quite often the only industry in the area. This could be very damaging for those rural communities and for those who rely on the business to thrive in order to make a living, such as logistics companies.

The situation is made worse by the fact that UK consumers drink a lot less bottled water than their European neighbours, leaving the British producers much more reliant on exporting. In Italy and Germany, people drink close to 200 litres of bottled water per year while the British get through just 36 litres per year.

But it is not all doom and gloom. There is a caveat in European regulations that would allow British water companies to continue selling in the EU, even if the Brexit withdrawal agreement falls apart. Existing EU countries have the prerogative of recognising mineral water sources from third countries, allowing them to be imported into the EU. That said, this situation would leave British bottlers dependant on other countries’ kindness to be able to continue exporting to the EU — a situation which would benefit multinational companies with sources and brands across the continent rather than smaller, local brands.

![]() The big players would be able to lobby for their British brands to be included on the ever important list of recognised natural mineral waters, while smaller sources could struggle to survive.

The big players would be able to lobby for their British brands to be included on the ever important list of recognised natural mineral waters, while smaller sources could struggle to survive.

Alexandre Nobajas, Lecturer in Human Geography and GIS, Keele University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Most read

- Astronomer from Keele helps take the first close-up picture of a dying star outside our galaxy

- Keele University signs official partnership with Cheshire College South & West

- Keele partners with regional universities to tackle maternity inequalities across the West Midlands

- Keele Business School MBA ranks in Top 40 for sustainability in prestigious global ranking

- Keele trains next generation of radiographers using virtual reality in regional first

Contact us

Andy Cain,

Media Relations Manager

+44 1782 733857

Abby Swift,

Senior Communications Officer

+44 1782 734925

Adam Blakeman,

Press Officer

+44 7775 033274

Ashleigh Williams,

Senior Internal Communications Officer

Strategic Communications and Brand news@keele.ac.uk.