Curious Kids: how can chickens run around after their heads have been chopped off?

This is an article from Curious Kids, a series for children of all ages. The Conversation is asking young people to send in questions they’d like an expert to answer. All questions are welcome: find out how to enter at the bottom.

If chickens run around after their head has been chopped off, does that mean their brain is in their bum? – Gaelle, age four, Bristol, UK

Thanks for the question, Gaelle. Chickens definitely don’t keep their brain in their bum. But just like humans, they have special fibres called “nerves”, which run like tiny wires all through their body, and some of them end near the surface of the skin. These nerves are what can make a chicken keep moving, even after its head has been chopped off.

Nerves are very important, because they make everything in our body work, including making our muscles move and helping us to feel things, with our sense of touch.

When you touch something, a little electrical current runs along a sensory nerve to your brain, to tell it what has happened – it’s a bit like hitting the light switch to let electricity run along the cable and into the light bulb.

When the signal gets to your brain, the brain decides what to do about it and sends another little electrical current back down a different nerve, called a motor nerve, with a message to the muscle to move.

Sometimes, the message doesn’t need to go all the way to the brain – it just goes as far as certain groups of nerves in the spinal cord. Then the decision about what to do goes straight back down the motor nerve to move the leg or arm.

For example, if you put your hand or foot down on something that’s really hot, your spinal cord will react to move your limb out of harm’s way – without even pausing to let your brain catch up. This is called a “reflex action”.

When you chop off a chicken’s head, the pressure of the axe triggers all the nerve endings in the neck, causing that little burst of electricity to run down all the nerves leading back to the muscles, to tell them to move. The chicken appears to flap its wings and to run around – even though it’s already dead.

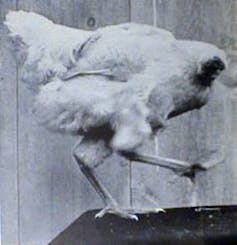

There was one cockerel who became known as Miracle Mike, who had his head chopped off and carried on living for another 18 months!

In his case though, the farmer who had tried to kill him had aimed too high, and had left a bit of his brain still working in the top of his neck, and that’s what allowed him to live.

That can happen to a bird, because its large eye sockets mean that there isn’t room inside its skull for all of its brain, so a bit of the brain lives inside the top of the neck.

Mike was kept alive for all that time by dripping milk and water into what was left of his throat, and he used to walk around just as he had always done.

Some scientists have noticed that frogs that have had their brain destroyed (which should kill them) will hop towards the light from a window. And if something is in their way, they will hop round it.

If the same frog is put in water it will try to reach the surface, and if a jar is put over it while it is in the water, it will dive down to get out of the jar and up to the surface.

It seems impossible, but actually it depends on which bits of the brain have been damaged. If the back parts of the brain, (the brain stem and medulla oblongata, for those who are interested) are not completely destroyed, then the frog can still do many movements.

Back to chickens: although they certainly don’t have their brain in their bum, they do have a little bit of the brain at the top of their neck, and lots of nerves in their spinal cord which respond to feelings in the skin, and make the muscles move – even when their head has been chopped off!

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to us. You can:

* Email your question to curiouskids@theconversation.com

* Tell us on Twitter by tagging @ConversationUK with the hashtag #curiouskids, or

* Message us on Facebook.

Please tell us your name, age and which town or city you live in. You can send an audio recording of your question too, if you want. Send as many questions as you like! We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

More Curious Kids articles, written by academic experts:

Why does English have so many different spelling rules? – Melania, age 12, Strathfield, Australia

How do you know that we aren’t in virtual reality right now? – Erin, 13, Strathfield, Australia

Jan Hoole, Lecturer in Biology, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Most read

- Keele University partners with Telford College and NHS to teach new Nursing Associate apprenticeship in Shropshire

- Emotion aware chatbot developed by Keele scientists offers transformative potential for mental health care

- First study of its kind sheds new light on Britain’s ‘forgotten’ World War Two decoy sites

- Keele cardiologist travels to Ethiopia to improve care for heart patients

- Keele academic wins prestigious prize for short story set in Stoke-on-Trent

Contact us

Andy Cain,

Media Relations Manager

+44 1782 733857

Abby Swift,

Senior Communications Officer

+44 1782 734925

Adam Blakeman,

Press Officer

+44 7775 033274

Ashleigh Williams,

Senior Internal Communications Officer

Strategic Communications and Brand news@keele.ac.uk.