Five films you need to watch to better understand radicalisation

Violent extremist ideologies are becoming more widespread, globally. It is clear that stemming this tide demands more than harsh policing and a “tough on crime” attitude. This is a deeper problem. Indeed, recently, UK Metropolitan police assistant commissioner Neil Basu argued that fighting extremism requires more than just policing and security measures. He suggested that sociologists and criminologists assume a leading role in tackling radicalisation, looking at factors like social exclusion, education and social mobility.

This is a positive development. But it’s worth remembering that filmmakers from around the world have been on the front line in exploring the reasons why young men and women are drawn into violent movements. And so when exploring the foundations of radicalisation, watching film is a good place to start. Film has the power to change how we see the world. Watching a film brings us face to face with people and situations we wouldn’t normally encounter.

This selection of films shows the problem of extremism in its complexity — moving away from Hollywood “villain and hero” tales, to examine how real people can become radicalised, as well as containing hopeful ideas for tackling the problem.

1. White Right: Meeting the Enemy (2017)

An astonishingly prescient documentary about the growing scourge of white supremacist terrorism, White Right is directed by Deeyah Khan, who was filming at the Charlottesville rally where anti-fascist protestor Heather Heyer was killed.

When interviewing white supremacists, Khan is frank about her Muslim identity and liberal politics. But instead of engaging the men she interviews in ideological debates, she focuses on their emotions, and highlights how their belief systems have impacted her personally.

The most striking instance of Khan’s approach is Ken Parker, an aggressive member of a neo-Nazi organisation. Having spent some time together, Khan reads Ken some racist abuse she received following a BBC interview. In a moving and transformational scene, Ken, visibly distressed, says, “I don’t want to hurt your feelings … I consider you a friend.”

For people like Ken, adherence to extremism gave him a sense of belonging. When confronted with the pain his ideology inflicted on a real person, he chose to leave. He is now an active member in his local African American Church.

2. The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2011)

Donald Trump may think that a travel ban on certain Muslim countries can stop terrorism in the US, but of course, it is impossible to tell who is, or will become, a terrorist from their nationality or skin colour.

This is the premise of Mira Nair’s film The Reluctant Fundamentalist: we don’t know whether the protagonist, Changez, is a terrorist or not.

The son of a blue-blooded but broke Pakistani family, Changez attends Princeton and obtains a coveted position in an elite Manhattan consultancy. He asserts: “I am a lover of America.” But this is the era of 9/11 – America is not a lover of Changez, his Pakistani passport, nor his “Muslim” appearance.

As societies, we reap what we sow. In the wake of 9/11, heightened, humiliating security measures and racial profiling alienated members of the Muslim community in the US.

The film also shows that there are different kinds of fundamentalism – how we treat those suspected of terrorism can tip into a kind of fundamentalist mania as well: “We can all be a little radicalised.”

3. Four Lions (2010)

Brass Eye creator Chris Morris’s latest political satire, The Day Shall Come, will be released on October 11, 2019, so it’s an excellent time to revisit Four Lions.

On reading reports of terrorist cells, Morris noted that they “contained elements of farce”. The jihadi band is just a “bunch of blokes”.

Starring the irrepressible Riz Ahmed, Four Lions lampoons the inefficacy of a haphazard gang of would-be jihadists and our fears of the terrorist bogeyman. The film also shows that the attractions of extremism for young British people are not religious, but instead connected a range of grievances, around capitalism and consumerism.

In one particularly hilarious scene, Ahmed’s character Omar launches into a tirade of astonishing verbosity:

We have instructions to bring havoc to this bullshit, consumerist, godless, paki-bashing, Gordon-Ramsey-taste-the-difference-specialty-cheddar, torture-endorsing, massacre-sponsoring, LOOK AT ME DANCING, PISSING ABOUT, SKY 1 UNCOVERED, WHO GIVES A FUCK ABOUT DEAD AFGHANIS? DISNEYLAND!

Ironic, then, that Omar blows himself up in a Boots chemist shop.

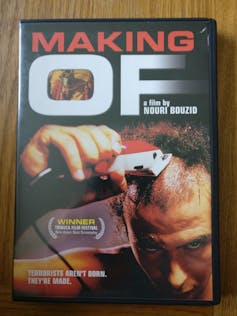

4. Making Of (2006)

Many accounts of radicalisation focus on Western countries, but films like Nouri Bouzid’s Making Of remind us that radicalisation is a global problem. This film addresses two issues that are consistently cited as key risk factors: youth and masculinity.

Making Of clearly outlines the push and pull factors that motivate extremism in young men: lack of job opportunities, feelings of shame and humiliation, brainwashing by extremist leaders. Most significant, the film suggests, is a lack of hope for the future.

Bhatha, the young radicalised man in the film, comes across not as an angry villainous terrorist, but as a confused and even vulnerable young man. One of the saddest moments in the film is when Bhatha says: “I don’t dream anymore.”

This chimes with anthropologist Scott Atran’s argument that aspirations are key in preventing radicalisation – we need to give young people hope, encourage their passions and dreams, and give them what he calls “a life of significance”.

5. Maurice Sweeney, I, Dolours (2018)

As the Irish border continues to be the sticking point in UK government’s Brexit policy, it’s a good time to revisit a conflict whose violence and devastation continue to affect the lives of Protestant and Catholic communities in Northern Ireland.

I, Dolours is an intimate documentary portrait of Dolours Price, an Irish Republican who became one of the most infamous members of the IRA in the 1970s and 1980s.

Price, who passed away in 2013, looks back on her days in the IRA. Jailed for participating in a car bombing of the Old Bailey in London in 1973, Price and her sister Margaret were the first IRA prisoners to go on hunger strike.

One of the most poignant aspects of Price’s move towards violent extremism is how it might have been avoided – as a schoolgirl, she was drawn first to the peaceful civil rights movement of African Americans like Martin Luther King.

Only after the brutality of the Burntollet Bridge attack did Price renounce peaceful methods of emancipation – showing that violence breeds violence.![]()

Maria Flood, Lecturer in Film Studies, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Most read

Contact us

Andy Cain,

Media Relations Manager

+44 1782 733857

Abby Swift,

Senior Communications Officer

+44 1782 734925

Adam Blakeman,

Press Officer

+44 7775 033274

Ashleigh Williams,

Senior Internal Communications Officer

Strategic Communications and Brand news@keele.ac.uk.