Curious Kids: why were there separate jobs for men and women in Victorian times?

A satirical photograph from 1901, where men’s and women’s dress and jobs are switched. Underwood & Underwood/Wikimedia Commons.

Alannah Tomkins, Keele University

Why were there separate jobs for men and women in Victorian times? – Malala Yousafzai class, Globe Primary School, London, UK.

Many Victorians thought that women and men had very different bodies and skills, meaning they were suited to different types of work.

They assumed that men had strong muscles and could think more rationally than women. So they thought that men were better suited to hard physical labour (such as coal mining) or to professional work needing lots of learning (being a doctor, for example).

They also thought that women were physically weaker, with less brain-power, but that they were good at emotional things such as showing sympathy and kindness.

This meant that women were mostly given simpler jobs (such as being an assistant to a man), or ones that required caring (like nursing). Women were also expected to do a lot of work around the house – but they didn’t get any money for this.

Victorian values

Now we understand that both men and women can be either muscly or weak, clever or not so clever, kind or cruel. But for most of the Victorian era, people thought it was normal for men and women to be treated differently, and judged by different standards.

Hello, Curious Kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Send it in to curiouskids@theconversation.com, along with your name, age and area where you live. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we’ll do our best.

This made life difficult for both men and women. Men were expected to be the “breadwinner”, which means earning enough money to pay the rent and buy enough food to eat, without asking their partner and children to work as well. This could be stressful, if their jobs did not pay very well. Unskilled men working as farm labourers, for example, might have been paid less than one pound per week.

Women were expected to be mothers and housekeepers – to cook meals, keep the house clean and tidy and look after everyone. This could also be tough, as women might get bored, or struggle to run their homes using just their husband’s wages. Some women would have needed to do some paid work as well, if their husbands weren’t earning enough.

Most adults were expected to get married and have children – so it was quite difficult to escape this pattern, where the man is the breadwinner and the woman is the housekeeper.

Hardworking women

Throughout the Victorian period, there were women who – by doing things that needed strength or intelligence – showed that they could be just as clever, strong or rational as men.

For example, Ada Lovelace was a mathematician – a pioneer who helped to make some of the first designs and programmes for computers. But she did this work for fun, rather than as a job, and was never given much credit for it during her lifetime.

Lots of poorer women were paid to do work at home, which meant they had to keep working for long periods of time, often more than 12 hours a day, as well as trying to look after their children.

But they earned so little that they often had to focus on doing the job, rather than being a mum. Women who made clothes at home often worked so hard they were actually called “sweated” labourers.

Being human

Being emotional is a human trait, not a male or female one, so of course there were men who found it difficult to cope with the expectation that they should be strong and rational all the time. Men who did not think they could show their feelings could become quite ill.

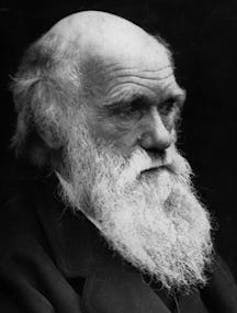

It is difficult to find examples of men who confessed to emotional struggles, but the famous scientist Charles Darwin was poorly throughout his life, and historians have suggested this was partly caused by stress.

By the end of the Victorian era, there was a growing sense that women should be able to do more of the things reserved for men – which included getting jobs, voting, holding elected office and being celebrated for their achievements.

For example, Josephine Butler, campaigned for women’s rights and, after her death in 1906, her name was added to a public memorial celebrating reformers.

The range of jobs that men and women could choose to do grew throughout the 20th century. Now, it’s pretty normal for a man to be a nurse, or a woman to be a soldier. And though some old-fashioned ideas about the roles of men and women still exist, there’s much more freedom for everyone to choose whatever job suits them best.

Curious Kids is a series by The Conversation, which gives children the chance to have their questions about the world answered by experts. When sending in questions, make sure you include the asker’s first name, age and town or city. You can:

- email curiouskids@theconversation.com

- tweet us @ConversationUK with #curiouskids

- DM us on Instagram @theconversationdotcom

Here are some more Curious Kids articles, written by academic experts:

-

How do ripples form and why do they spread out across the water? – Rowan, aged six, UK.

-

How does our brain send signals to our body? – Aarav, aged nine, Mumbai, India.

Alannah Tomkins, Professor of History, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Most read

Contact us

Andy Cain,

Media Relations Manager

+44 1782 733857

Abby Swift,

Senior Communications Officer

+44 1782 734925

Adam Blakeman,

Press Officer

+44 7775 033274

Ashleigh Williams,

Senior Internal Communications Officer

Strategic Communications and Brand news@keele.ac.uk.