Rosa Parks Barbie doll reflects popular misunderstanding of civil rights struggle

The Rosa Parks Barbie (centre) with other figures from the Inspiring Women Series. From L to R: Katherine Johnson, Sally Ride, Frida Kahlo and Amelia Earhart. Mattel, Inc.

David Ballantyne, Keele University

The toy company Mattel recently released a Rosa Parks Barbie doll as part of its Inspiring Women Series, a promising addition to a collection that presents strong female role models to children. But the way the company describes Parks points to broader problems of remembering the American Civil Rights Movement by focusing only on the most famous figures and events.

Despite concerns about the dolls presenting unrealistic body shapes, commemorating women such as Parks in doll form is a positive step. Mattel notes research showing that from a young age, girls tend to view themselves as less bright than boys (the so-called “dream gap”), so the Parks doll is, again, a helpful way of countering this.

The Inspiring Women series is also racially diverse, which matters, especially for non-white children. By presenting to children female role models from a range of ethnicities, Mattel is adapting to an increasingly diverse group of consumers.

More than just ‘a seamstress’

While toy company descriptions may be an odd place to look for accurate histories, Mattel’s write up of Parks’s life arguably misses a chance to highlight other inspirational women central to the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

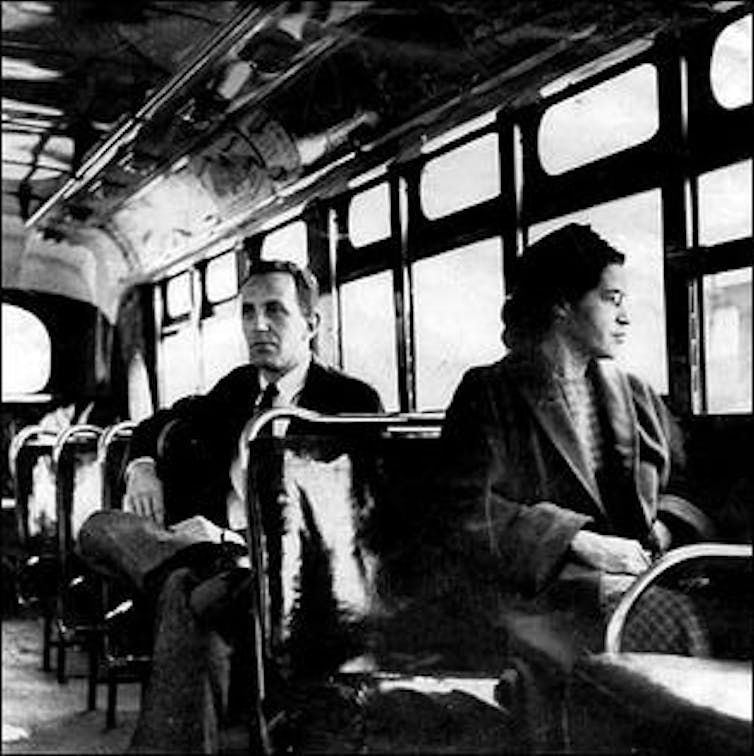

Each Barbie comes in packaging that tells the doll’s story – and this packaging could give a fuller tale of Parks’s activism. Mattel’s website now describes Parks as “a seamstress and dedicated activist leading up to December 1, 1955” – the date of her arrest for not giving up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. (The company had faced some criticism for an earlier claim that before December 1955 Parks “led an ordinary life as a seamstress.”)

Indeed, Parks had actively opposed racial injustice for decades and was the secretary for her local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (then the leading group promoting black rights in the US).

In 1955, she trained for two weeks at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, a centre where a who’s who of civil rights leaders honed their skills. Even her refusal to give up her seat was not so surprising: black activists in Montgomery had complained about conditions on city buses several times in the years before 1955.

Nor was Parks the only strong woman in the story. After her arrest, a group called the Women’s Political Council played a vital role in pushing for a bus boycott. The boycott offers a great chance for Mattel to mention other empowered women who, like Parks, “paved the way for generations of girls to dream bigger than ever before.”

Making sense of the Civil Rights Movement

Mattel’s description of Parks’s life after 1955 reflects a widespread habit of presenting the Civil Rights Movement as having a neat and successful mid-1960s end point. Its website notes that after her protest, “it would still take another nine years and more struggles before the 1964 Civil Rights Act overruled existing segregations [sic] laws.”

In this story’s simplest form, African Americans like Parks took a stand against racial injustice, a mass social movement emerged, and then President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act into law. These laws outlawed racial segregation in public life and provided meaningful support for black citizens who wanted to vote. But many historians disagree with this account.

Ending the civil rights tale with the 1964 and 1965 laws is understandable. Success stories are easier to tell. But stopping there misses the messiness (and incompleteness) of later civil rights gains. Well beyond the 1960s, Parks didn’t see the civil rights struggle as fully won.

Take racial segregation in schools. The US Supreme Court’s famous 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case ruled legally-mandated public (read “state”) school segregation unconstitutional. Yet it took until the end of the 1960s, the threat that the federal government would cut off school funding, and several more court cases for meaningful racial integration to occur in formerly segregated schools in the American South. Even then, the court stepped back from pushing school integration across the country in the next decade.

Mattel’s Inspiring Women series is laudable. But while children’s toy companies obviously can’t be expected to write complex civil rights accounts, Mattel could tell consumers a slightly fuller story about Parks that mentions other inspirational women and her lifelong commitment to activism. In doing so, it might also help young people better understand American civil rights history.![]()

David Ballantyne, Lecturer in American History and Director of the David Bruce Centre for American Studies, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Most read

Contact us

Andy Cain,

Media Relations Manager

+44 1782 733857

Abby Swift,

Senior Communications Officer

+44 1782 734925

Adam Blakeman,

Press Officer

+44 7775 033274

Ashleigh Williams,

Senior Internal Communications Officer

Strategic Communications and Brand news@keele.ac.uk.