Comment | Uncovered: the WW2 ‘Scallywag Bunkers’ that were Britain’s last-ditch line of defence

Keele's Dr Jamie Pringle and Dr Kristopher Wisniewski write for The Conversation UK.

June, 1940. France was in desperate peril from the invading German armies. The majority of the British Expeditionary Force, sent to fight alongside their allies, had been evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk. On June 4, British prime minister Winston Churchill turned to his stirring oratory, delivering his most famous address:

We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.

With the fall of France, there would be no capitulation. With the Empire and free forces of the defeated Allies, Britain would fight on. Yet the Battle of Britain was still to come, and there was every expectation that an invasion was imminent. Some 14 million Ministry of Information leaflets were posted through letterboxes: “If the Germans come, by parachute, aeroplane or ship, you must remain where you are.”

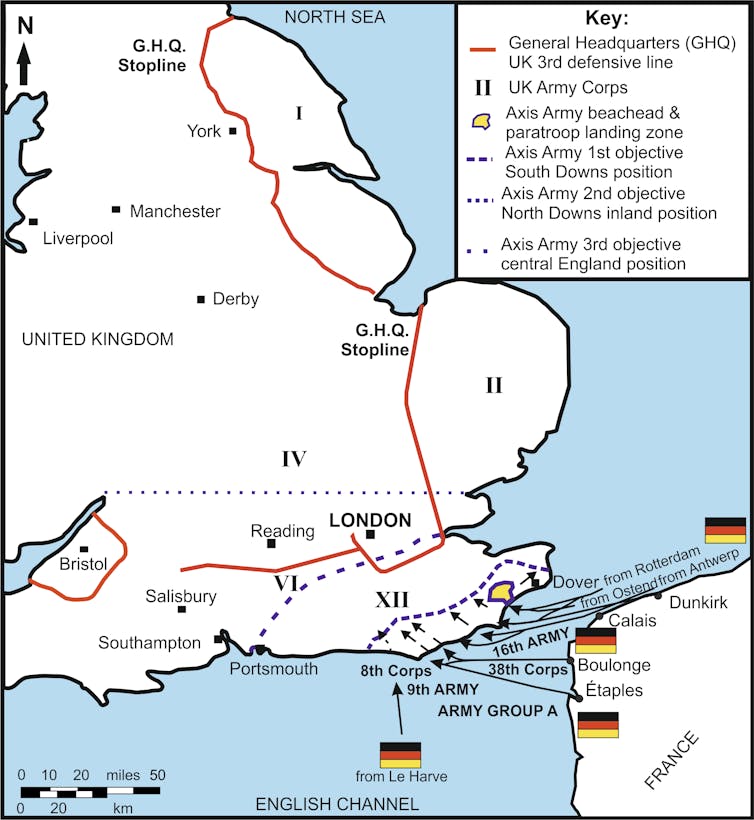

It was expected that Unternehmen Seelöwe (Operation Sealion) would follow, a German seaborne invasion backed by aerial assault. Defensively, Britain was in a poor state. The British Expeditionary Force had left behind huge amounts of military hardware after Dunkirk, and preparations for the defence of Britain had to be put in place by all means necessary. The Local Defence Volunteers were raised – a scratch force that Churchill would insist be renamed “The Home Guard”.

Defensive preparations included the construction of a series of holding lines to slow down the invader. Lines of concrete bunkers, tank obstacles and trenches were hastily built and, starting at the coast, followed in progressive lines inland.

These would allow, in the face of invasion, the retreating home forces time to link up with reserves to hold the General Head Quarters (GHQ) Line, protecting London and the industrial Midlands (Figure 1) and buying time for the Royal Navy to cut off reinforcements and supplies.

A clandestine force

While the Home Guard patrolled with make-do pikes, another, more clandestine force was being recruited on the direct orders of Winston Churchill: “last-ditch” units possessing intimate knowledge of the land and firearms – a force that could emerge silently, and skilfully melt away from any invaders.

For years, the activities of these men have been subject to speculation, their operating bases and activities shrouded in mystery, with no official acknowledgement of their wartime activities. And with the recent loss of the last known member there are no witnesses to explain their role and operations.

Our new scientific investigation, just published in the Journal of Conflict Archaeology, however, sheds new light on these specially trained, highly secretive, clandestine “Auxiliary Units”. Tasked to fight guerrilla operations behind enemy lines after invasion, their activities included sabotage and the assassination of high-ranking Axis officers.

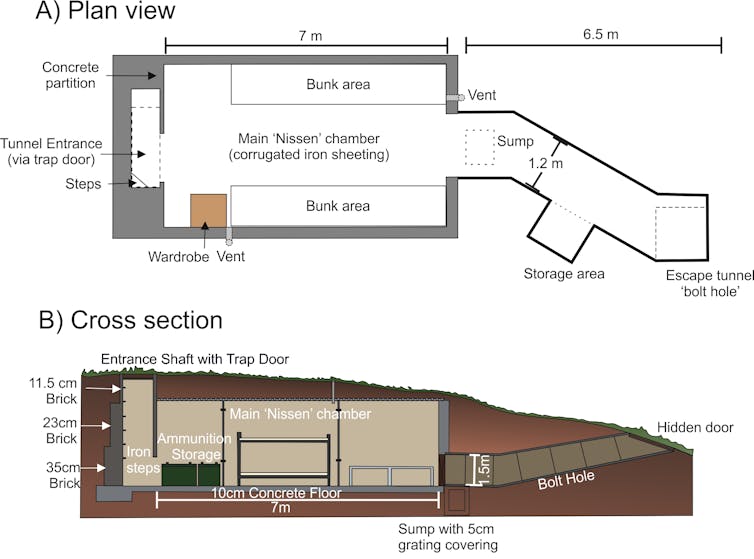

Just enough records survive to indicate that patrols comprised four to eight civilians with expert local knowledge – farmers, country landowners, gamekeepers, even poachers. After training at Coleshill House, they were to operate from below-ground Operational Bases (OBs) (Figure 2), set in remote locations in order to avoid detection.

Likely survival rates for these men were as low as 12 days, which may be why OBs were sometimes called “Suicide Bunkers”. To the men themselves, they were known as “Scallywag Bunkers” – after their proposed “Scallywagging” activities. Nationally, only a few survive, encountered only by accident today .

Uncovered

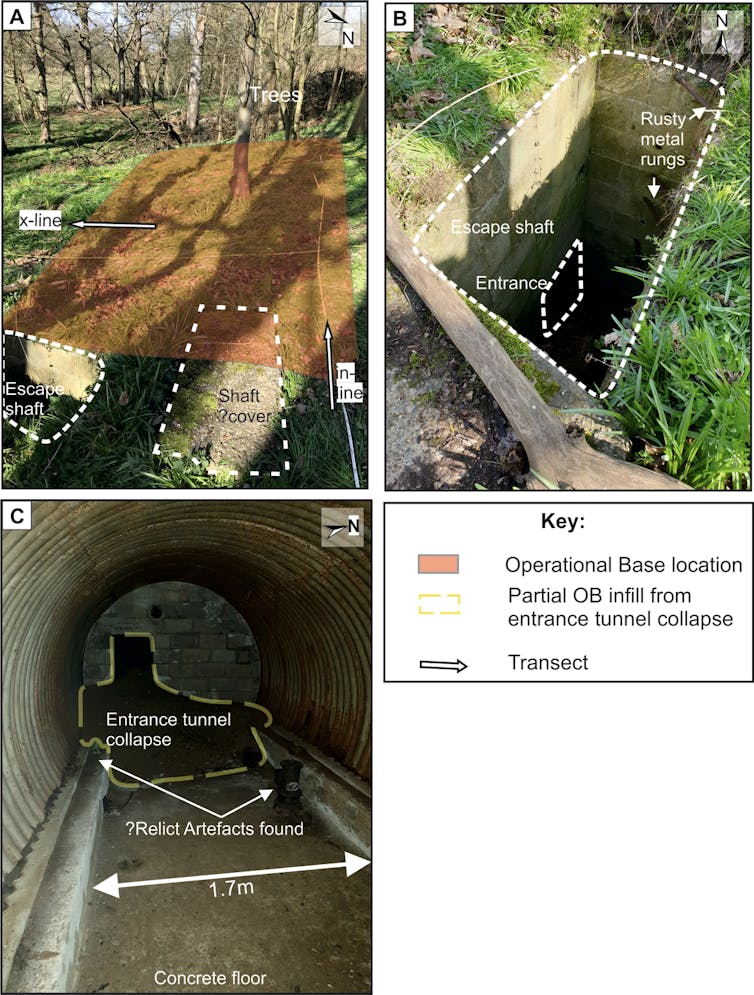

Our research looked at three surviving Operational Bases (OBs) on private land in Suffolk in various states of preservation – just three from the 36 originally thought to have existed. The three OBs studied were all deliberately positioned for “scallywagging”, close to railway lines/main routes, or large country houses, the likely billets of high-ranking German officers targeted for assassination.

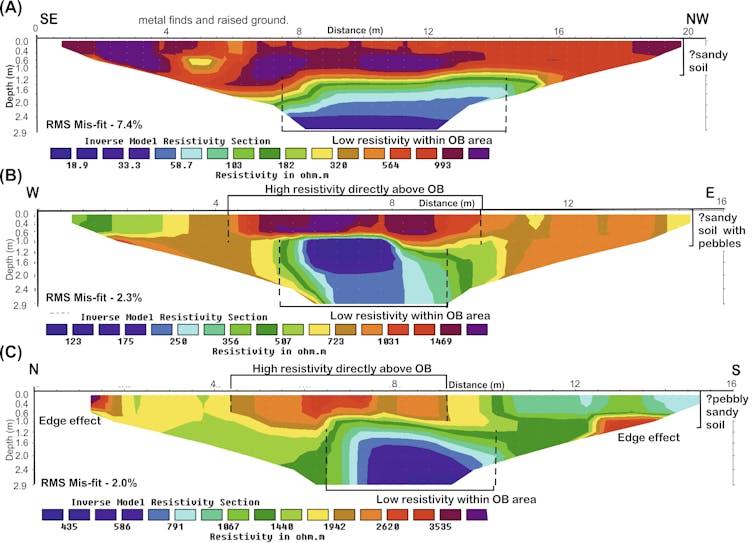

We conducted surface surveys, including recording of any artefacts, before carrying out near-surface geophysical surveys (Figure 3) to pinpoint OB locations.

These techniques had previously been undertaken by us to identify second world war UK air-raid shelters, and allied and Axis prisoner-of-war escape tunnels.

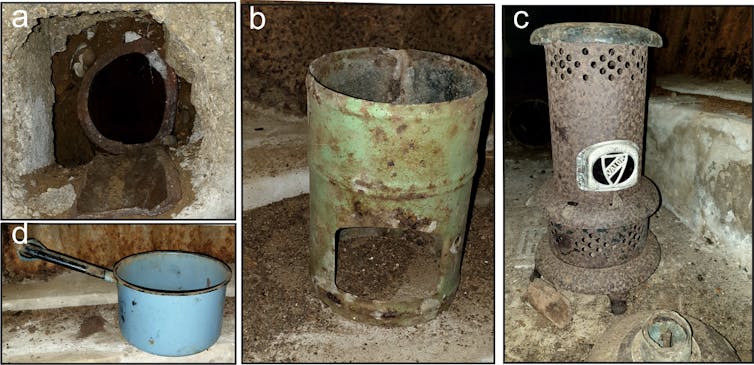

Some limited intrusive investigations were carried out at two bases, discovering escape hatches, intact chambers (Figure 4) and artefacts that included heating stoves, lighting and cooking implements – evidence of planned long-term occupation (Figure 5). This is the first such study to evidence the physical activities of this clandestine force.

Ultimately, it is a matter of conjecture how effective the Auxiliary Units would have been if the German invasion had happened. Certainly, unlike the earnest but largely unskilled Home Guard, the Auxiliary Unit comprised accomplished landsmen, ready to bring their skills to bear. Their “scallywagging” activities would surely have been disruptive, buying vital time for regular troops to assemble at the GHQ line for the final defensive stand.

Would it have worked? A 1974 wargame employing surviving German generals, suggested Operation Sealion would ultimately have been a failure, hampered by a lack of air and sea support. There is no doubt that that Auxiliary Units would have played their part – and the surviving OBs remain silent witnesses to their commitment to deadly “scallywagging”.![]()

Jamie Pringle, Senior Lecturer in Geosciences, Keele University; Kristopher Wisniewski, Geoforensic Researcher (Staffordshire University) and Lecturer in Chemistry (Keele University), Staffordshire University, and Peter Doyle, Head of Research Environment, London South Bank University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Most read

- Keele University partners with Telford College and NHS to teach new Nursing Associate apprenticeship in Shropshire

- Emotion aware chatbot developed by Keele scientists offers transformative potential for mental health care

- First study of its kind sheds new light on Britain’s ‘forgotten’ World War Two decoy sites

- Keele cardiologist travels to Ethiopia to improve care for heart patients

- Keele academic wins prestigious prize for short story set in Stoke-on-Trent

Contact us

Andy Cain,

Media Relations Manager

+44 1782 733857

Abby Swift,

Senior Communications Officer

+44 1782 734925

Adam Blakeman,

Press Officer

+44 7775 033274

Ashleigh Williams,

Senior Internal Communications Officer

Strategic Communications and Brand news@keele.ac.uk.