Why revolutionary Russia backed Turkish nationalists over communists

Bulent Gökay, Professor of International Relations, Keele University

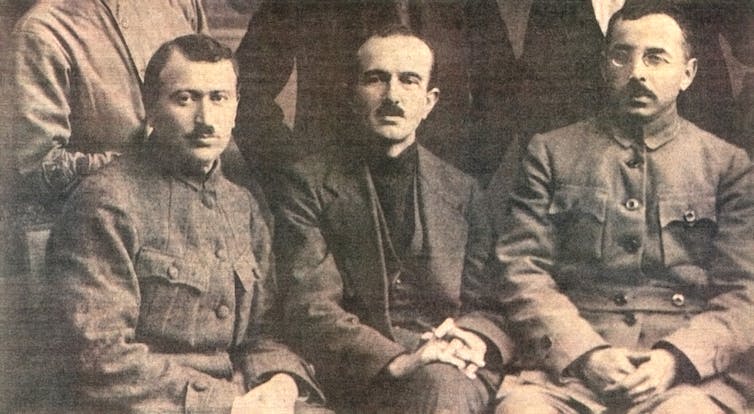

Communist Party of Turkey founder Mustafa Suphi (right) met a mysterious fate when he tried to take on the Ankara government. Wikimedia Commons Bulent Gökay, Keele University

Communist Party of Turkey founder Mustafa Suphi (right) met a mysterious fate when he tried to take on the Ankara government. Wikimedia Commons Bulent Gökay, Keele University

Soon after the Ottoman Empire officially ceased to exist at the end of World War I, there soon sprung up an energetic new Turkish national resistance movement. In its efforts to found a new Turkish state, it attracted major international support – and among its most crucial allies was the young Bolshevik government in Moscow.

Both the Turkish nationalists and the Russian Bolsheviks found themselves threatened by the Western imperial powers. The 1920s were the heyday of anti-imperialist revolution for the Bolsheviks, and the notion of an alliance with majority Muslim nations made perfect sense – a chance to simultaneously unite against the imperial West in the Muslim world and to transform Muslim society along the Bolsheviks’ preferred ideological lines.

On December 7 1917, almost immediately after they came to power, the Bolsheviks issued their Appeal to the Toiling Muslims of the East, which assured the Muslims of Russia that “your beliefs and customs, your national and cultural institutions, are free and inviolable” and called on the Muslims of the east to overthrow the imperialist robbers and enslavers of their countries.

At the Comintern’s Second Congress in 1920, Lenin went so far as to suggest that, with “the aid of the proletariat of the advanced countries”, it might be possible for Asia to skip the capitalist stage and “go over to the Soviet system, and, through certain stages of development, to communism”.

In this promising atmosphere of friendship between the Bolsheviks and anti-imperialist Muslim Turks, a number of left-leaning groups started to gain momentum in Anatolia in the 1920s. Most significant among these were the Green Army Association (Yesil Ordu Cemiyeti) a popular grassroots radical movement, and the Communist Party of Turkey, organised in 1920 and led by Mustafa Suphi, a Turkish communist who had been in Russia since the start of World War I.

Signing the Treaty of Moscow, March 1921. Wikimedia Commons

Signing the Treaty of Moscow, March 1921. Wikimedia Commons

The Soviet government and Turkey’s new nationalist government were drawn together by mutual fear of the Western powers in the region and, on March 16 1921, they signed the Treaty of Moscow. In its preamble, it committed both countries to the “struggle against imperialism”. Thus began the long era of Soviet-Turkish friendship, officially confirmed in December 1925 with a non-aggression pact in December 1925.

Aid to – or an alliance with – a local government or a “bourgeois” national movement aimed against “imperialists” always posed the danger that the non-communist “client” might turn against the local communists. In practice there was no escaping from this dilemma, and in Turkey as elsewhere, the Soviets many times took the side of the friendly government as opposed to their Communist fellow travellers. While the Communist Party of Turkey enjoyed political and financial support from Moscow from the outset, it was clear that when push came to shove, that relationship would always be less important than the Soviets’ bigger strategic concerns.

Murder on the Black Sea

In September 1920, soon after the party was founded, Mustafa Suphi and the other leading party members decided to shift the centre of their activities to Turkey proper. In late 1920, they left Baku and set out across the Black Sea. They got no further than Trabzon, on the Turkish coast. On January 28 1921, Suphi and 15 other leading communists were apprehended, put on a boat and sent back to Batum in Georgia. Immediately after that boat set out, another boat left the harbour and overtook it. Of what happened next, all that is known is that no-one on the first boat survived.

The available documents confirm that the nationalist Ankara government had a substantial role in this incident – and the Bolshevik government apparently did not share the Turkish communists’ optimism. When the news arrived in Moscow, the Soviet politburo forwarded an official statement to inform the members of the Soviet communist party, warning them of the “dangers of left-wing and adventurist initiatives”.

Ultimately, this incident was simply noted and put aside by both governments. That their relationship survived the murder of Turkey’s leading communists speaks volumes about how the early Soviet era unfolded in the “near east”. The Moscow government faced a very particular dilemma: how to support both anti-communist national liberation movements who were fighting common enemies while also sponsoring and organising local communist groups against those same nationalist governments.

![]() In the end, it more often than not came down on the side of strategic pragmatism rather than ideological purity. As Turkey’s Kemalist leadership openly started to root out all communist activity in the country, world communist gatherings issued their protests – but through it all, Moscow and Ankara stayed on good terms until the start of the Cold War.

In the end, it more often than not came down on the side of strategic pragmatism rather than ideological purity. As Turkey’s Kemalist leadership openly started to root out all communist activity in the country, world communist gatherings issued their protests – but through it all, Moscow and Ankara stayed on good terms until the start of the Cold War.

Bulent Gökay, Professor of International Relations, Keele University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.