Astronomers have found their paradise, and it’s the coldest and most remote point in Antarctica

Harvepino / shutterstock

Jacco van Loon, Keele University

Antarctica. The name evokes images of bitter extremes, an environment unkind to humans. Stories of polar explorers battling with the weather and perishing on their way back to safety. Why would astronomers choose to go there?

To get the best views of space, space itself is the best place to be. Here on Earth, one can escape the grip of our zest for luminescence and seek out a remote corner of the world where nights are still black except for the distant stars. Or one can climb a mountain, to leave below much of the bubbly air that blurs images of space, and especially humid air that blocks our view of space altogether.

This is where you can find the most powerful telescopes, on the summits of mountains, islands in desert or ocean. Chile. Hawaii. But Antarctica? Surely not?

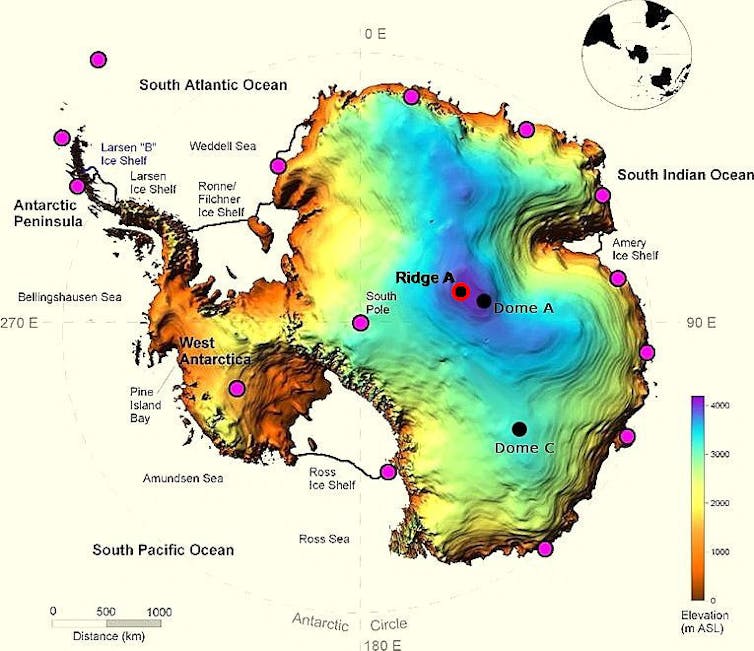

In fact, the continent is ideal. And one of its coldest and most remote spots of all, a featureless place named “Ridge A” that sits near the high point of a vast polar desert, might just be the best place on Earth to look into space.

Ridge A is high and dry. HEAT / University of Arizona, Steward Observatory

The area has exceptionally clear skies. While the “Roaring Forties” are the nightmares of round-the-world sailors, and the Furious Fifties and Screaming Sixties loudly announce a point of no return, the South Pole itself is in actual fact an overwhelmingly calm place. It’s highest recorded wind speed is just 58mph, barely even a gale.

Weather systems – a euphemism typically reserved for ugly storms – are powered by relatively warm air and the rotation of the Earth. The vast ice cap that covers the Antarctic continent means the South Pole is far from any warm ocean waters. And, if you are standing still at the South Pole proper, you would rotate around your own spine, and it would take you 24 hours to do so. Hardly a wild whirlwind.

Antarctica is of course cold. How cold? The lowest temperature ever recorded on Earth was experienced near the South Pole: -89.2℃. This is the result of the total absence of sunlight for nearly six months in a row. While such conditions pose severe risks to humans, and to the lubricants used to keep mechanical parts operating, they also carry a great benefit for astronomers: moisture freezes.

Water vapour is the main greenhouse gas in the Earth’s atmosphere, and it is removed almost entirely at such prolonged, exceedingly low temperatures. This clears up the air, rendering it more transparent – especially to infrared light. The cold conditions higher up in the atmosphere lead to a depletion of ozone molecules, which block ultraviolet light. The upshot is that Antarctic skies are also more transparent to ultraviolet light. For astronomers like me, the South Pole is already halfway to space.

Why Ridge A beats the South Pole

You can climb a high mountain in the Himalayas or the Andes, and leave half the air below you. But the air pressure drops too, which makes residential life above 6km altitude impossible. The low temperatures on Antarctica, and its general flat – if elevated – expanse, cause the atmosphere to sink, forming a heavy blanket near the surface that has a higher pressure than would be expected on mountain summits of that height elsewhere. It is thus more bearable to humans, at least in that regard.

The low humidity does, however, cause problems to both humans and electronics alike, not the least in the form of electrical shocks. Such collapsed atmosphere makes it also much easier to climb above it. Topping at just over 4000m, Ridge A is a mere 8 degrees away from the South Pole, which is at 2800m altitude. It thus combines all the benefits of cold, thin and calm air and months of pitch-black skies.

Scientists at work in -45C temperatures on Ridge A. Video: Geoff Sims, UNSW.

After a series of experimental telescopes have been deployed at other polar stations, astronomers have now set their eyes on Ridge A. The site is a superb base for “traditional” telescopes operating at optical and the adjacent ultraviolet and infrared frequencies, and also for telescopes operating at the highest radio frequencies. But the ability to stare at the same spot for months on end also offers unique possibilities for seeing farther out into space than ever before.

While conditions are not for the faint-hearted, the calm weather and easy terrain of Ridge A relieve some of the construction difficulties and operational challenges one encounters on steeper mountains – and certainly those one would face in space. This makes the site relatively accessible – by air at least.

![]() And while it is steadily becoming cheaper to go into space, it will never beat the economics of staying on Earth. It is just a matter of time until a multi-national research organisation, a university consortium, or a wealthy benefactor bites the bullet and decrees that one of the most powerful telescopes on the planet shall be built on Ridge A, to bring space down to Earth.

And while it is steadily becoming cheaper to go into space, it will never beat the economics of staying on Earth. It is just a matter of time until a multi-national research organisation, a university consortium, or a wealthy benefactor bites the bullet and decrees that one of the most powerful telescopes on the planet shall be built on Ridge A, to bring space down to Earth.

Jacco van Loon, Astrophysicist and Director of Keele Observatory, Keele University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Most read

Contact us

Andy Cain,

Media Relations Manager

+44 1782 733857

Abby Swift,

Senior Communications Officer

+44 1782 734925

Adam Blakeman,

Press Officer

+44 7775 033274

Ashleigh Williams,

Senior Internal Communications Officer

Strategic Communications and Brand news@keele.ac.uk.