The bottled water industry’s healthy origins

Evians on Lake Geneva was originally a spa town. shutterstock.com

Alexandre Nobajas, Keele University

Huge outcry ensued from my recent article about how Brexit would hurt Britain’s bottled water industry. The outcry wasn’t to do with Brexit. Instead, it was over the very existence of a bottled water business.

There were environmental concerns relating to the huge amount of plastic that the industry involves, not to mention the fuel used in transporting the bottles. There were also suggestions that the industry is a “scam” in countries where people can access perfectly good water from the tap.

So who had the great idea of selling something which, in principle, is so cheap and accessible? Some varieties can cost as much as £2,000 a bottle.

The origins of bottled water have to be traced back to when spas had a resurgence in popularity in Europe and its colonies in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was a time when tap water was unsafe to drink and, although people were unaware of this, the groundwork was laid for many of the household names in the bottled water industry today.

Taking the waters

A change in social, cultural and medicinal practices resurrected the Greco-Roman tradition of “taking the waters” for health purposes. Thanks to the development and popularisation of hydrotherapy by famous physicians such as Priessnitz and Kneipp, and the special properties of waters found in certain locations, such as their chemical composition or their temperature, formerly derelict spas flourished again and new ones were built.

Spa towns such as Vichy, Evian and Vittel in France, Bath and Buxton in England, San Pellegrino in Italy, Caldes de Malavella in Catalonia, and Carlsbad (Karlovy Vary) in what is now the Czech Republic became the hotspots. Wealthy people flocked to them to relax, socialise and seek treatment for a variety of ailments.

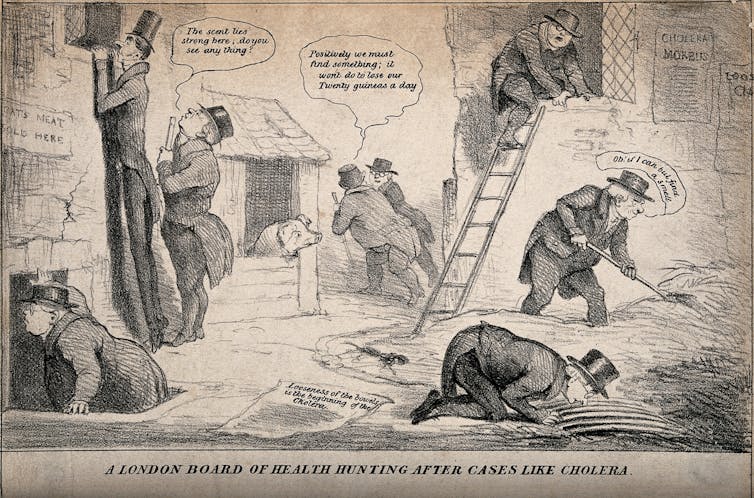

The period when spa culture flourished in the West coincided with the height of the Industrial Revolution, when cities became crowded and waterborne diseases were commonplace. Epidemics such as cholera or typhoid fever ravaged cities and caused serious health conditions, which often led to hundreds of deaths due to the drinking of contaminated water.

Cholera was a major problem but its causes were unknown. Wellcome Library no. 1998i, CC BY

It is therefore not surprising that going to a spa town – usually located in the countryside and with water originating from unpolluted sources – dramatically reduced the chances of getting ill and helped recovery from existing illnesses. But treatments were expensive, as they were lengthy, lasting several weeks and in some cases months.

The bottling business

Such lengthy treatments were not available to everyone, not only because of the cost, but also due to the necessary time commitment. This meant that busy people couldn’t always finish their treatments. Consequently, some asked bath houses if they could subscribe to a periodic delivery of water from the spa for a fee in order to continue the treatment throughout the year. And those who could not afford to go to the spa also wanted to have access to its water.

Even though some bath house owners were reluctant at first, many agreed and started shipping water to cities. Initially it was at a high cost, as water is very heavy and difficult to transport. Labels and watermarks on bottles developed in response to the illegal trade that sprung up where fake bottled water was sold to those who could not afford to buy the real deal.

With the expansion of the railway and the general improvement of communication systems, transportation costs became progressively lower and more people were able to afford mineral water in cities. This in turn increased its production and sale. It led to the start of businesses which sold water from sources not linked to spas, and therefore not necessarily marketed as medicinal; they just sold water which was cleaner than publicly sourced water during a time when epidemics were rife.

The business boomed until urban and domestic water sanitation methods improved, especially with the spread of chlorination techniques during the first decades of the 20th century and the discovery of how illnesses could be identified and treated. Both advances had an important impact on the spa water industry and the bottled water business. Many struggled or disappeared altogether.

![]() But recent years have seen the resurgence of the industry, led by technological and lifestyle changes. The brands and tradition were already there, so with some effective marketing and good distribution networks, bottled water has become popular again. But that is a different story.

But recent years have seen the resurgence of the industry, led by technological and lifestyle changes. The brands and tradition were already there, so with some effective marketing and good distribution networks, bottled water has become popular again. But that is a different story.

Alexandre Nobajas, Lecturer in Human Geography and GIS, Keele University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Most read

Contact us

Andy Cain,

Media Relations Manager

+44 1782 733857

Abby Swift,

Senior Communications Officer

+44 1782 734925

Adam Blakeman,

Press Officer

+44 7775 033274

Ashleigh Williams,

Senior Internal Communications Officer

Strategic Communications and Brand news@keele.ac.uk.